The Language of Silence [Part 1]

How ecocide and genocide intersect on California's largest lake

Littoral zone: the shallowest part of a lake encompassing the shoreline and associated vegetation; the area most vulnerable to loss.

At the northernmost tip of North America’s oldest lake stands a small hillock that used to be an island. The island, known in Before-time as Bo-no-po-ti, was encircled by tule reeds, massive clusters of blue-green stems with their feet submerged in clear waters. Tipped with starbursts of copper flowers and towering over most humans, the tule created marshlands embracing all manners of swimming, wading, and nesting birds and other native wildlife: tule elk, tule perch, and the world’s largest garter snake.[i]

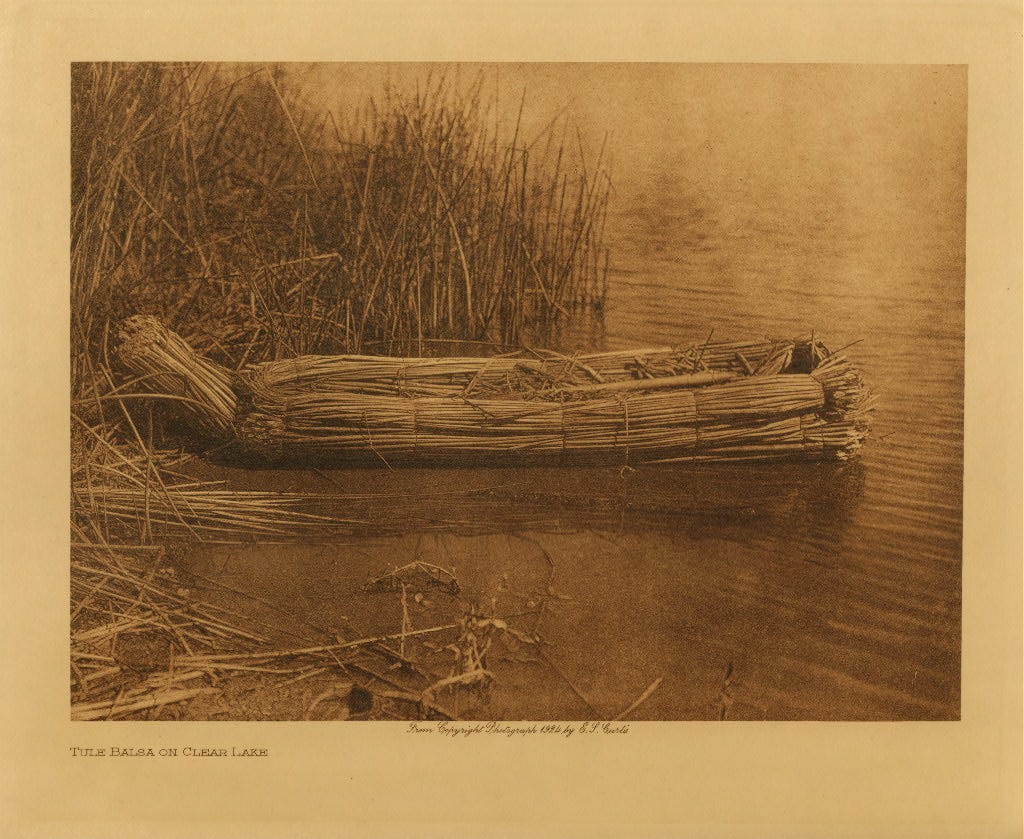

In Before-time, the lake was called Ka-ba-tin and its overlooking volcanic mountain named Kno-htai for its resemblance of a woman (htai) wearing a woven hat (kno). When the waters of Kabatin encircled Bonopoti, locals caught steelhead trout and Pacific lamprey year-round, and each spring partook of lakeside fish spawnings by the millions, orgies of glistening splittail and hitch overcrowding streams feeding the lake. The island’s people, the Ba-don-na-poti, ate tule tubers and wove tule into everything that one could possibly craft with water reeds: dolls and duck decoys, baskets and boats, clothing and houses.

The Badonnapoti lived in close proximity to dozens of other tribal bands whose aboriginal rights for the lake and lakeside territories stretched back over twelve thousand years, bands grouped under the misnomer “Pomo:”[ii] the Shigom and Xabahnapoh on the eastern shores and the Qulahlapoh on the west; the Danoxa, Kaiyo-Matuku, Xowalek, and Yobotui to the north, the Kulanapo to the south, later and the Kamdot[iii] to the southeast; the Kaogoma on Elem island, and the Koi in the western marshes, along with the Howalek, Boalke, Kómli, and many others.

My mouth does not know how to pronounce these names, and my fingers only recently learned how to type them. This is a purely scientific form of ignorance.

Ecologists are taught the Latinate names of everything we can see: flowering and non-flowering plants, fungi, insects, amphibians, reptiles, fish, crustaceans, birds, mammals, nematodes, bacteria, archaea, protists, and viruses. We learn the names of soils, minerals, and geological formations, biological assemblages, and climatological regimes. But we learn, and can recount, virtually nothing about the humans who knew these same creatures and phenomena far more intimately, and for many more centuries, than our discipline has been in existence.

According to scientists, the languages of the peoples who inhabited Kabatin’s lands are extinct.[iv] Their descendants say these once-spoken tongues are sleeping, waiting to be woken. Although I have yet to find someone who can speak fluently in the Before-time languages, I am peeling back the layers of this loss, one syllable at a time.

In the After-time, the Badonnapoti had the horrible luck of being the scape goat tribe for celebrated young mid-nineteenth century pioneers Andrew Kelsey[v] and Charles Stone. Driven out of Midwestern towns angered by their illegal land-grabbing schemes, Kelsey and Stone ultimately settled by Kabatin lake on land purchased from Captain Salvador Vallejo, a military commander credited with founding Napa and Lake counties and leading “field operations under the Mexican flag against dissident Indian tribes,”[vi] setting the stage for later displacement of Natives onto small land parcels known as rancherias.[vii] The pioneers took full advantage of local resources: hundreds of tribespeople built Kelsey and Stone’s adobe house and corral, tribal women pounded flour for them, and tribal men looked after their cattle herds.

While in their twenties, Kelsey and Stone distinguished themselves with cruelty: starving and enslaving local tribes, selling them off like livestock or forcing them to work on their ranch, hauling tribal men to gold mines and feeding their rations to other miners,[viii] punishing tribal members who dared to hunt for food by hanging them by their hands from trees or shooting at them to impress guests, whipping those who asked about what happened to their kinsmen, and whipping parents who failed to deliver their daughters to be sexually abused.[ix]

In the fall of 1849 – and historical accounts differ about what, precisely, defined the tipping point for the beleaguered lakeside tribes – braves of the Hoolanapo clan decided they “might as well die one way as another,”[x] and planned an attack on Kelsey and Stone. Stories vary as to whether the final straw was Kulanapo Chief Augustine’s wife being taken forcibly as a concubine, or the recent murder of a clansman, or the plan to drive elders and children to Sacramento, or the deaths of kinsmen in the gold fields, or the fear of retribution from a foiled cattle rustling attempt; whether preparations the night before involved Chief Augustine’s wife pouring water onto the pioneer’s gun powder, or braves stealthily hiding their guns, or house slaves removing all the weaponry; or whether Kelsey was dispatched with a spear, an arrow, or an arrow and a stone; or if Stone was brained with a rock or killed with a knife.

The sole indisputable fact remaining is the killing and burying of the two abusers, after which the responsible braves, feeling “they had their liberty once more and were free men,”ix quit the premises to join relatives around the lake.

Word of the killings spread from one pioneering settlement to another, and over the next two months groups of armed settlers brutalized, shot, or burnt every Indian not otherwise claimed as a slave in nearby Napa and Sonoma valleys.[xi] Shortly thereafter, U.S. Army Lieutenant J.W. Davidson and Second Lieutenant George Stoneman,[xii] under the orders of Pacific Division General Persifor F. Smith led a company to “cut the Clear Lake Indians to pieces” for the murders.

The men found the lake deserted except for the Badonnapoti community on their island, and when Bonopoti island proved to be out of rifle range, reinforcements were ordered. Captain Nathaniel Lyon, the regional U.S. Cavalry regiment commander in Monterey, secured whale boats and cannons from San Francisco and mountain howitzers from Benicia. Five days after departing Benicia, Captain Lyon’s expedition joined Davidson and Stonemans’ dragoon companies detached to the western shore of the lake. Two Kaogoma were forced into guiding the men.[xiii] As the dragoon proceeded, firing the cannon into the brush and shooting tribal members on sight, clanspeople fled to the northern lake corner, to Bonopoti island.

On May 15, 1850, regiment soldiers from the First Dragoon and local settlers attacked the island surrounded by shallow spring waters. “The Indians, who, perceiving us once upon their island, took flight directly, plunging into the water, among the heavy growth of tula.”[xiv] Unleashing the full force of their artillery, the regiment took no prisoners: clubbing, stabbing and shooting people as they tried to swim away, and pursuing villagers into the tule marsh. They killed children, and mothers holding infants, by slamming bayonets through their bodies and tossing them into the water. The rancheria and all food stores were burnt.[xv]

“The tula was thus thoroughly searched, with severe protracted efforts, and with most gratifying results,” reported Captain Lyon, boasting that he killed between sixty to one hundred people.

The soldiers soldiered on. Apparently wiping out an entire village was insufficient retribution. After the Bonopoti island massacre, the militia murdered their Kaogoma guides (one shot, one hung) and proceeded to the Yohaiyak[xvi] community, at least seventy-five souls, living over twenty miles away. Upon seeing the regiment, the Yohaiyak fled to a densely thicketed island in the middle of the Russian River, where it was impossible to mount an effective defense.

“The island soon became a perfect slaughter pen,” recounted Lyon.

It took the remaining tribes five days to gather the dead.

One six-year-old girl survived the Bonopoti massacre. Her name was Ni’ka. She hid underwater, breathing through a tule reed straw until it grew dark.

When she emerged, the water was filled with blood, her people gone.[xvii]